Post #229

1060 words – 5 minutes to read

Summary: The annual report (CCRSO) released by Public Safety Canada reveals important and troubling aspects of our criminal justice system.

We have examined previous editions of this publication from Public Safety Canada here and here. There are few changes in the patterns in those earlier posts, but this most recent report (2020 data) is in a new format that focuses more on graphics.

Crime rates

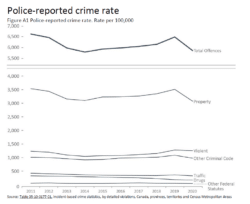

A reasonable person looking at the historical data in this report would not conclude that there is any kind of upsurge in crime in this country. The rate of violent crimes per capita reported to police has risen in the last few years but is still well below the levels of the past 20-30 years.

Six provinces and all 3 territories showed an increase in crime rate from 2016 to 2020, some of them (for example New Brunswick) large, while 4 provinces showed decreases. Quebec has by far the lowest rate and showed the largest decrease. The rate of reported crime in Quebec (3600/1000,000 people) is less than a third of the rate in Saskatchewan (12400) which is in turn triple the rate in Ontario (4400). What accounts for these huge variations? We do not know.

Violent crime

Non-sexual assaults account for about 60% of all violent crime charges. Women are more often victims of violence in part because they are the victims of the overwhelming majority of sexual assaults. However about 75% of murder and attempted murder victims are men. Self-reported violent crime (as opposed to those reported to police) is far more common for young people – 15-24 and 25-34 rates are far higher than among older groups.

Charges

The rate of adults being charged with a crime had been rising prior to 2020, but then dropped significantly, probably due to Covid lockdowns. Charge rates are still below where they were from 1998 to 2012.

Administration of justice charges, mainly things like bail or parole violations, account for 22% of all criminal charges. The court system itself creates a lot of the work that it then has to deal with by imposing unreasonable conditions in the first place. Given over-crowded courts and long delays in hearings, this is an area where reform has long been recommended but has not happened.

The most common criminal charges among the total of 300,000 in 2020 include common assault (30,000), impaired driving (30,000), theft (29,000), failure to comply with a court order (27,000), and breach or probation (27,000). These five categories account for half of all charges. Compare these to homicide (320), prostitution (10), sexual assault (3500) and drug possession (5000).

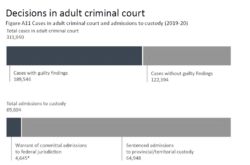

Many charges dropped

It is shocking to find that 40% of all criminal charges in Canada end with no conviction. More than 100,000 people a year have their lives badly disrupted, and incur huge costs financially and in other ways, when there apparently was never good evidence that they actually committed a crime.

Other indicators

About half of all jail sentences in Canada are for 30 days or less. One might ask what can possibly be achieved by sentences this short, other than totally disrupting people’s lives and quite possibly costing them jobs, housing, custody of children and the like?

Youth crime continues to decline and charges against people under 18 have dropped by 60% in the last ten years. These changes happened largely because of different choices about what to do with young people in trouble with the law. These data suggest that we could do something similar with adults if we had a mind to redesign our systems for dealing with wrongdoing.

Consistent with that point, Canada’s overall incarceration rate continues to be lower than other English-speaking countries, but significantly higher than most countries in Europe. Incarceration rates have much more to do with policy choices than with crime levels.

The correctional system

For the first time, provinces in 2020 spent more on jails than the federal government did on prisons. Federal prison costs have been roughly stable around $2.5 billion for quite a few years while provincial jail costs have increased by 46% (22% in real terms) over the last 10 years to $2.7 billion. This increase has come even though the number of people in provincial jails has remained roughly stable.

The average daily cost per prisoner in federal prisons has increased from $319 in 2015-16 to $345 in 2019-20 (or $126,000 per year). The cost for women is about 80% higher. On the other hand, managing a prisoner in the community (on parole) costs about 80% less, or about $35,000 per year.

Ten years ago about half of provincial prisoners had been sentenced and half were awaiting trial. Now about 2/3 are awaiting trial. Despite the media coverage, the evidence is that more people are unable to get bail than in earlier years.

Indigenous people make up 27% of the federal prison population, a proportion that continues to grow. They are more likely than others to be in custody instead of serving their sentence in the community. They are also more likely to be in higher security institutions and to be placed in segregation. The latter is so even though admissions to segregation fell by nearly 50% over the last few years, since courts ruled that the segregation system was unlawful.

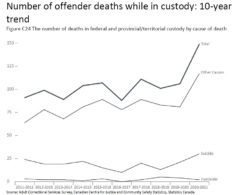

The number of deaths in jails and prisons in Canada has soared. No explanation is provided for this.

Parole

The proportion of prisoners released on day parole increased from 2014 to 2019 but has decreased the last two year. It never rose above 38%, which means a majority of prisoners do not get paroled. On average prisoners who are paroled serve about 37% of their sentence prior to day parole and 45% prior to full parole. Once again, results in both these categories were worse for Indigenous people.

More than 90% of day paroles are completed successfully; about 1 in 200 ends due to another crime. For full parole, which lasts much longer, just under 90% end successfully while 2 to 3% are terminated due to another crime. The success rates are much lower for those held until statutory release. For many years now in Canada, parole has been highly effective yet greatly underused.

Pardons/record suspensions

This system seems to be failing, which might have been the intent of the Conservatives when they changed it. Applications for ‘record suspensions’ have dropped very significantly, even though the pardon program was and remains highly successful. The net result is more Canadians having to carry criminal records with a net loss to public safety.

The CCRSO report is an essential source of information, and much of what it reveals raises important questions about the efficacy and equity of our system.

The John Howard Canada blog is intended to support greater public understanding of criminal justice issues in Canada. Blog content does not necessarily represent the views of John Howard Society of Canada. All blog material may be reproduced freely for any non-profit purpose as long as the source is acknowledged. We welcome comments (moderated) and suggestions for content. Contact: blogeditor@johnhoward.ca

Back

Comments are closed here.