Post #265

1000 words; 4 minutes to read

ELECTION SPECIAL

Informed comment on criminal justice issues in the current federal election.

By Tyler King, doctoral student, and Anthony Doob, Professor Emeritus at the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies, University of Toronto. We appreciate the collaboration with the Centre on this and future posts.

We are both old-fashioned (though only one of us is old). When people talk about a social problem and then come up with a specific – and often costly – solution, we want to first know what the actual problem is. These days, this approach seems decidedly old-fashioned, especially to politicians who seem more interested in catchy slogans.

Pierre Polievre’s “jail not bail” slogan suggests, without evidence, that his policy would “stop criminals convicted of three serious offences from getting bail, probation, parole or house arrest” (https://www.conservative.ca/poilievre-to-crack-down-on-liberal-violent-crime-wave-with-three-strikes-and-youre-out-law/). There is one rather serious problem with this proposal: he simply asserts that the justice system has allowed crime to run out of control.

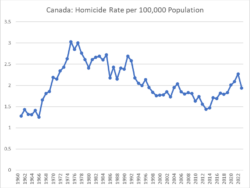

Being old-fashioned, we first tried to understand the bail “problem” by looking first at Canada’s most serious offence: homicide (see Figure 1). (Homicide has the advantage of being more likely to be reliably recorded than other offences).

In the past 60 years, homicide rates have varied over time. They hit a high just before Canada abolished capital punishment and then decreased substantially. Nobody suggests that the abolition of capital punishment in the mid-1970s caused the decline in homicides in Canada. It is even less logical to suggest that Trudeau was responsible for the small increase after 2015. Similarly, it is not likely that the increase in the homicide rate that started near the end of the Harper period had anything to do with Harper’s sentencing policies, just as nobody would give Trudeau credit for the dip in 2023.

Source: Created by authors from Statistics Canada data

Politicians who claim our bail laws are too lenient tend to argue we should punish first (before a trial) and worry later about whether they are guilty.

They seem to forget that there are two parts of the story: the law and its administration. The (federal) law allows – and in certain cases effectively encourages – some people to be detained prior to trial. But it is largely the provinces who administer the criminal law. It is the police, crown attorneys (largely provincially appointed) and judicial officers (again, provincially appointed) who are responsible for decisions on bail. It doesn’t make sense to make “bail laws” a topic of debate during a federal election when the power to change who is actually detained currently lies largely with provincial officials.

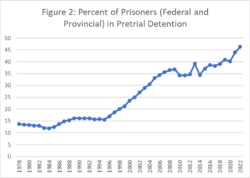

Proponents of stricter bail seem to be suggesting that it is rare that people are detained in prison before their trials. This is wrong. As can be seen in Figure 2, beginning in the mid-1980s and developing most clearly in the mid-1990s (when the Liberals were in power in Ottawa), Canada has been imprisoning more and more people before they are found guilty of anything. The principle, it seems, is that it is easier to punish them if you don’t have to bother with proving their guilt.

In the early 1980s, about 12% of Canada’s prison population consisted of legally innocent people awaiting trial. But in 2022 almost half (46%) of Canada’s total prison population, and more than 70% of those in provincial jails, are people in pretrial detention — people who have not been found guilty of anything. In 2022 and 2023 half of all criminal charges did not result in a conviction, so that means thousands of innocent people are being jailed in Canada, often for weeks or months.

Source: Created by authors from Statistics Canada data

The data do not support the conclusion that we are “soft” on people charged with offences. Quite the opposite.

In Ontario, in 2022 the cost of holding someone in pretrial custody for one month averaged $11,163 (about $140,000 per year). Since we are not very good at predicting who will commit an offence while awaiting trial in the community — or at any time for that matter — we are spending a lot of money incarcerating people who did not offend and would not reoffend, money that could be spent more productively on policies that actually reduce crime.

Indeed, there is a relationship between imprisoning people and the likelihood of them committing crime. Pretrial detention may actually increase the likelihood that a person will offend in the long term.

Well-designed research studies have examined what happens when similar accused persons are either detained or released prior to their trial. It appears that pretrial detention creates more crime (see Criminological Highlights 17(5)#3: https://irp.cdn-website.com/63cb20a6/files/uploaded/CrimHighlightsV17N5.pdf). This doesn’t show up in the short term because those being detained are in jail. But in the long run, those who are detained are more likely to be arrested for new offences. Simply stated, prison often makes it harder for people to reintegrate into society.

But why don’t we notice that we are creating crime with such an unfettered use of pretrial detention? A small portion of those released prior to trial commit new offences. We hear about them. But what if a person is detained in custody prior to the trial and then is released at the end of their sentence or they are acquitted or have their charges dropped, as happens quite often? If these people are charged with a new offence they aren’t deemed “newsworthy,” since they are just fully free people who are rearrested. The accused on pretrial release gets all the attention.

Our bail laws currently make it clear that an accused can be detained if they are likely to commit an offence. But none of us are perfect in making that prediction.

Other than suggesting that we just throw away the notion that people are innocent until proven guilty in a legitimate court of law, are the proposals to get rid of pretrial release in certain circumstances sensible?

Being old-fashioned, we think that public policy should focus on making Canada a better (and safer) place to live. We rather like s. 9 of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms: “Everyone has the right not to be arbitrarily detained or imprisoned.” We should not change it to a system where an unproven accusation can lead to automatic imprisonment.

About this blog: The John Howard Canada blog is intended to support greater public understanding of criminal justice issues. Blog content does not necessarily represent the views of the John Howard Society of Canada. All blog material may be reproduced freely for any non-profit purpose as long as the source is acknowledged. We welcome comments (moderated). Contact: blogeditor@johnhoward.ca.

Back

Comments are closed here.