Post #210

730 words; 3 minutes to read

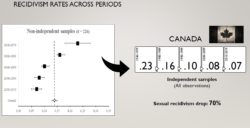

Summary: A meta-analysis of 116 studies shows that recidivism rates among people convicted of sex offences in Canada have dropped dramatically over the last 40 years and are now very low.

Audio summary by volunteer Hannah Lee.

Canada is one of a number of countries that has put in place extra constraints and controls on persons convicted of sexual offences. (We use the term ‘sex offenders’ here for convenience, recognizing that this group includes a very diverse set of crimes. These additional restrictions include the provincial and national sex offender registries, controls on travel and passports, as well as restrictions on being able to receive a pardon. These measures were justified at the time as being needed because there was a higher rate of reoffending among this group. However that claim was never based on solid evidence and was disputed by experts.

More recent evidence has shown a very different picture. In fact, as a group sex offenders have a very low rate of reoffending – much lower than for most other types of crimes, a finding consistent across many studies in many places. Moreover, as a new study shows, reoffending rates for people with convictions for sex crimes have dropped very substantially over the years. Canadian researchers have played leading roles in uncovering both these facts.

New meta-analysis

The large drop in reoffending rates is shown in a recent study by Patrick Lussier (Université Laval) and Evan McCuish (Simon Fraser University). They are leading an international team looking at these issues.

Their paper provides a review of the increasingly harsh measures adopted in regard to sex crimes. These measures, they say, are intended to address high recidivism rates. As the authors write, For more than 80 years, sex offender recidivism (SOR) has generated fear, media attention, public outrage and frustration with the criminal justice system.

But what if those rates are actually quite low and have been declining since well before these additional restrictions began? Perhaps the outrage and fears are misplaced, and the restrictions unjustified.

Big declines in recidivism

The Lussier and McCuish study involved combining results from many different previous studies using sophisticated statistical analyses. Previous Canadian research provided them with 88 different estimates involving a total or nearly 30,000 people with convictions. These studies followed people for years after their previous charge – typically 5 to 10 years. Some studies used being rearrested as the measure of recidivism, while others used a new conviction.

The report notes that between 1990 and 2010, sex crimes reported to police dropped by about 45%, consistent with a large drop in crime rates generally in Canada and other countries. At the same time, reoffending, or recidivism for people convicted of sex offences declined even more.

In fact, the rate of recidivism in these studied declined by 70% from studies done before 1980 to the most recent research. And these declines could not be attributed to differences in the study methods or populations.

They conducted a similar analysis with US data, involving many more studies and many more people. Again, there was a very large decline in recidivism rates from earlier to more recent studies.

Additional punitive measures likely not useful

As befits researchers, the authors conclusions are careful. They ask whether all the additional effort that currently goes into managing this group is really warranted. Do we need all of these people to report to police every time they buy a car or change their address or leave the country? Do we need police officers to be verifying their situation at least once a year? Do the risk assessment tools used to determine things like parole eligibility reflect the facts or are they rooted in obsolete data?

In suggesting that our current policies are expensive and unproductive, this analysis is consistent with quite a bit of other research that suggests that many of the ‘special measures’ for sex offenders are motivated by politics rather than by evidence. Sadly, it is easy for politicians to play on public fears and look as if they are doing something when in reality the result is wasteful use of police time and unnecessary restrictions on people who are not a threat to public safety.

For example many questions have been raised, including by police, about whether Canada’s SO registries either prevent crime or help solve crimes. Maintaining the registry does use quite a bit of police time, and the Supreme Court recently ruled that being on a registry imposes substantial hardships on people. That balance may make sense where the risk is high, but it does not for most people who, as this research shows, are at very low risk to reoffend.

About this blog: The John Howard Canada blog is intended to support greater public understanding of criminal justice issues. Blog content does not necessarily represent the views of John Howard Canada. All blog material may be reproduced freely for any non-profit purpose as long as the source is acknowledged. We welcome comments (moderated). Contact: blogeditor@nulljohnhoward.ca.

Back