Post #194

700 words; 3 minutes to read

Audio summary by volunteer Averi Brailey

Since 1995, Canada has introduced a wide range of mandatory minimum sentences for various crimes, with a another big expansion under the Harper government. Between 1999 and 2021 the number of mandatory minimums went from 29 to 134!

A new report by the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) estimates the costs of one of these increased penalties, but also has fascinating comments on other aspects of mandatory minimums, which have been controversial all along.

Mandatory minimums are expensive

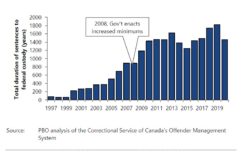

Let’s start with the money. The PBO uses one example – the three year minimum for firearms offenses, created in 2008. Using data from the Correctional Service, they estimate that the creation of this sentence has led to people serving nearly 1200 more years in prison than they would have previously. In any given year about 680 more people are in prison and 465 more on parole, at an estimated cost of $98 million per year. Not only are sentences considerably longer (see chart) but those convicted of these charges wait longer to get parole – on average 60% of their sentence vs the 33% that is legally mandated, and the less than 40% that is the average for all parolees.

Court declaration seems not to matter much

Like many other mandatory minimum provisions, this one was declared unconstitutional by the courts including, in this case, by the Supreme Court in 2015. Yet ‘This declaration of unconstitutionality had no discernable impact on sentences for the offence.’

This surprising finding, PBO concludes, is because the mandatory minimum led to a shift in how judges thought about sentencing for this crime. And as has been shown elsewhere, sentencing changes tend mostly to ratchet up.

‘The normative effect of minimum sentences can be seen in the increase in the frequency of sentences in excess of the three-year minimum sentence following the enactment of the minimum sentence. It is also demonstrated by the continuing elevation of sentenced time in federal custody after [this provision] was declared unconstitutional.’

Wider effects of sentences

Mandatory minimums have even wider effects. ‘The availability of a minimum sentence may influence the offence that prosecutors charge and the plea agreement they will accept. Conversely, [it] may affect the willingness of the defendant to proceed to trial, and their willingness to accept a plea agreement.’

In fact, after the introduction of the mandatory minimum in this case there was little change in the number of ‘Convictions…over the relevant period. Second, the increase in sentenced time in custody for the specific offence is reflected in an increase in sentenced time in custody for weapons offences generally.‘

Discriminatory effects

Mandatory minimums also disproportionately affect Indigenous and Black people. ‘Black people are 3.5% of the Canadian population but received 24% of the increase in sentenced time in federal custody. Indigenous people are 2.6% of the Canadian population but received 22% of the increase in sentenced time in federal custody.’

Finally, the report notes that the effects of mandatory minimums depend on the specific crimes. Sometimes they are offences that very few people commit ( for example, treason). In other cases prosecutors do not charge that offence (e.g. drug trafficking in or near a school). In still others, such as attempted murder with a firearm, the mandatory minimum does not result in more severe sentences than the offenders would have received anyways.

Government promised change but has not acted

Although the Liberals promised to take action on mandatory minimums in 2015, it is only now, 7 years later, that they have a bill that proposes to eliminate some of them – 20 in total meaning that most will remain in place.

This bill has been sharply criticized by many justice advocates because it falls so far short of what the Liberals promised, is inconsistent with the results of public consultations on this issue a few years ago, and does not even match their own admission in introducing it.

‘Sentencing laws that have focused on punishment through imprisonment have disproportionately affected Indigenous peoples, as well as Black Canadians and members of marginalized communities. MMPs have also resulted in longer and more complex trials, including an increase in successful Charter challenges and a decrease in guilty pleas, which has compounded the impact for victims, who are more often required to testify. They have failed to deter crime.’

Back